Compilation vs. vectorization, search engine edition

Virtual function calls are quite expensive, which is why database systems have been looking into ways to avoid performing one or more virtual function calls per record when processing a query. Two main approaches have proved successful: compilation and vectorization. With compilation, the database engine dynamically generates code specifically for the query that needs to be processed. With vectorization, the database engine processes large batches of records at once to amortize the cost of virtual calls. Everything you always wanted to know about compiled and vectorized queries but were afraid to ask is a good resource if you’d like to learn more.

This topic has been less studied in Information Retrieval. Mostly because it’s not a problem in what is considered the standard case. The Information Retrieval literature focuses on evaluating disjunctive and conjunctive queries where all clauses are term queries. You don’t need virtual function calls to solve this problem since the only kind of iterators that you need to deal with are iterators over postings lists. This is one reason why PISA is fast (the other main reason being recursive graph bisection): it doesn’t need to deal with the overhead of virtual function calls and the compiler can aggressively inline performance-sensitive code, in-turn enabling other optimizations (“inlining is the mother of all other optimizations”).

However, you can build more interesting search engines if you allow your disjunctive/conjunctive clauses to be anything: term queries, range queries, or even other disjunctive/conjunctive queries. This is what Lucene does, but also Tantivy or Vespa, so this isn’t anecdotal. These engines implement document-at-a-time (DAAT) retrieval on top of an iterator abstraction that looks like this:

/**

* Iterator over an ordered set of doc IDs.

*/

interface DocIdSetIterator {

/**

* Return the current doc ID of this iterator, initially -1,

* Integer.MAX_VALUE when the iterator is exhausted.

*/

int docID();

/**

* Given a target that is greater than the current doc ID, advance to the

* first doc ID that is greater than or equal to this target and return it.

*/

int advance(int target);

}

A query is something that can produce such iterators over matching documents. For instance, term queries produce iterators over postings lists and disjunctive queries produce iterators that merge several iterators on the fly, typically using a min-heap ordered by doc ID.

While the ability to combine any kind of query through disjunctive/conjunctive queries is very powerful, the natural approach requires making the advance(target) function call virtual. Since queries make at least one virtual call on an iterator per candidate document, this adds up to non-negligible overhead. If - like Lucene - you want to support other ranking functions than BM25, then it gets even worse as it’s 1+ more virtual call per evaluated document to compute the score.

The main workaround to this that I am familiar with is specialization. For intance, you can specialize the case when all disjunctive clauses are term queries (the case that the Information Retrieval literature focuses on). This can be seen as a form of poor man’s compilation, where common cases are generated statically at compile-time rather than dynamically at runtime. Both Lucene and Tantivy do this to some extent. I am not aware of someone having tried to specialize at runtime, this would certainly be an interesting experiment.

But Lucene has also recently been exploring vectorizing query evaluation with some success, by processing batches of doc IDs at once, instead of a single doc ID. On paper, vectorization is appealing, as it amortizes the cost of virtual function calls over many doc IDs, produces more memory-friendly access patterns, makes efficient use of CPU pipelining and allows talking advantage of SIMD instructions. The downside is that you should avoid branching while processing a batch of data to take full advantage of vectorization, which may result in more work being done than necessary.

Vectorizing conjunctive query evaluation

I chose to focus on conjunctive queries, because conjunctive query evaluation tends to be a bit simpler, and also because they are more interesting with regards to vectorization, since the key aspect of conjunctive query evaluation is to cancel evaluating a document as soon as we find one clause that doesn’t match this document. Intuitively, this requires lots of branching, which doesn’t play well with vectorization.

Before reading further, I would recommend getting familiar with Ding and Suel’s paper on block-max indexes and the block-max AND algorithm in particular (section 7.3 in the paper). One thing worth noting about Lucene’s index format at this point is that postings lists are organized into blocks of 128 doc IDs and term frequencies. Doc IDs are encoded either with FOR-delta (which means that deltas between consecutive doc IDs are packed into as few bits as required) if they are sparse, or as bit sets if they are dense (akin to roaring bitmaps). Score impacts are aligned with postings blocks, so Lucene can tell what the maximum score that a doc ID in a block may produce before decoding this block.

Below, I describe a simplified version of Lucene’s current algorithm for evaluating conjunctive queries, which is inspired from block-max AND.

interface Scorer {

/** Return the iterator of this scorer. */

DocIdSetIterator iterator();

/** Compute the score of the current doc ID. */

float score();

/**

* Advance skip data without decoding doc IDs. This is what is called

* NextShallow in the block-max indexes paper. This returns the end bounday

* of the impact block that contains the target doc ID.

*/

int advanceShallow(int target);

/**

* Compute the maximum possible score for doc IDs between the last target

* passed to advanceShallow and the given doc ID (inclusive).

*/

float getMaxScore(int docIdUpTo);

/**

* Return a batch of doc IDs and scores including the current doc ID and up

* to the given doc ID inclusive, and advance the iterator to the first doc

* ID after this batch.

*/

(int[], float[]) nextDocsAndScores(int docIdUpTo);

}

/**

* Evaluate the conjunction of the given scorers, loading hits into the given heap.

* Scorers should be ordered by ascending number of matches.

*/

void evaluateConjunctiveQuery(Scorer[] scorers, Heap topkHeap) {

// Use the scorer with te least number of matches to lead iteration

Scorer lead = scorers[0];

for (int windowMin = 0; windowMin < Integer.MAX_VALUE; ) {

// Use impact blocks of the leading clause as windows of doc IDs to process

// at once. This effectively means that the batch size is the same as the

// block size in postings lists, 128.

windowMax = lead.advanceShallow(windowMin);

for (int i = 1; i < scorers.length; ++i) {

// Advance the cursor into skip data on other clauses, but ignore how

// their impact blocks line up with the leading clause.

scorers[i].advanceShallow(windowMin);

}

// For each clause, compute the maximum score contribution of this clause,

// plus the next ones.

float[] cumulativeMaxScores = new float[scorers.length];

for (int i = cumulativeMaxScores.length - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

cumulativeMaxScores[i] = scorers[i].getMaxScore(windowMax);

if (i + 1 < cumulativeMaxScores.length) {

cumulativeMaxScores[i] += cumulativeMaxScores[i + 1];

}

}

if (cumulativeMaxScores[0] <= topkHeap.minScore()) {

// This window of doc IDs may produce ties at best, let's skip it.

windowMin = windowMax + 1;

} else {

if (lead.iterator().docID() < windowMin) {

lead.iterator().advance(windowMin);

}

// Compute a batch of matching doc IDs and their corresponding scores on the

// leading clause. This typically returns 128 entries (the size of postings

// blocks in Lucene). Doc IDs and term frequencies are decoded in batches.

// The computation of BM25 scores uses SIMD instructions.

(int[] docs, float[] scores) = lead.nextDocsAndScores(windowMax);

for (int i = 1; i < scorers.length; ++i) {

// Hits whose score is not greater than or equal to minRequiredScore have

// no chance to make it to top-k hits

float minRequiredScore = topkHeap.minScore() - cumulativeMaxScores[i];

// Only keep docs and scores whose score is greater than minRequiredScore.

// This is branchless and takes advantage of SIMD instructions.

(docs, scores) = filterByScore(minRequiredScore);

// Filter doc IDs that are also matches of the given clause, adding the

// score of this clause to the score. This is currently still

// implemented using branches and virtual calls to

// DocIdSetIterator#advance and Scorer#score as batching this operation

// hasn't proven to give significant benefits (yet?)

(docs, scores) = applyRequiredClause(scorers[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < docs.length; i++) {

topkHeap.insert(docs[i], scores[i]); // overflows if more than k entries

}

windowMin = lead.docID();

}

}

}

The batch size that is used to vectorize query execution at runtime is aligned with the block size of postings. In practice, this means that the batch size is 128. This may sound small, but this is important to avoid decoding many more blocks of postings compared with the original block-max AND algorithm.

The most interesting thing to observe about this algorithm is probably how it computes scores of candidate doc IDs before checking if these doc IDs match all clauses. In contrast, the original block-max AND algorithm only starts computing scores after confirming that a doc ID matches all clauses. Our benchmarking suggested that we save more work by computing scores first, which in-turn helps skip advancing the iterator on other clauses if the produced score is low, than by advancing other iterators first and only computing scores of documents that match all clauses. This is something that Lucene started doing before it started vectorizing query execution, and it turns out that score computation can be more efficiently vectorized than filtering a list of candidate doc IDs based on whether they match another clause, which is convenient. What we observe on queries that match many documents (which tend to be the harder queries, ie. queries that drive tail latencies) is that there are often not many documents left after the first call to filterByScore.

Our benchmarking suggested that this algorithm performs better than block-max AND on queries that have many hits, but slower on queries that have few hits. So Lucene’s implementation is actually a bit more sophisticated and evaluates the first k matches with traditional DAAT conjunctive query evaluation (which it internally refers to as “doc-first”) before moving to this vectorized algorithm (which it refers to as “score-first”).

Disjunctive query evaluation builds on block-max MAXSCORE and the same primitives. In each window, clauses are partitioned into essential and non-essential clauses using local score upper-bounds. Essential clauses are evaluated exhaustively using the same nextDocsAndScores primitive. Then non-essential clauses are applied on the (int[] docs, float[] scores) buffers by adding up their score to scores of matching doc IDs.

Benchmarks

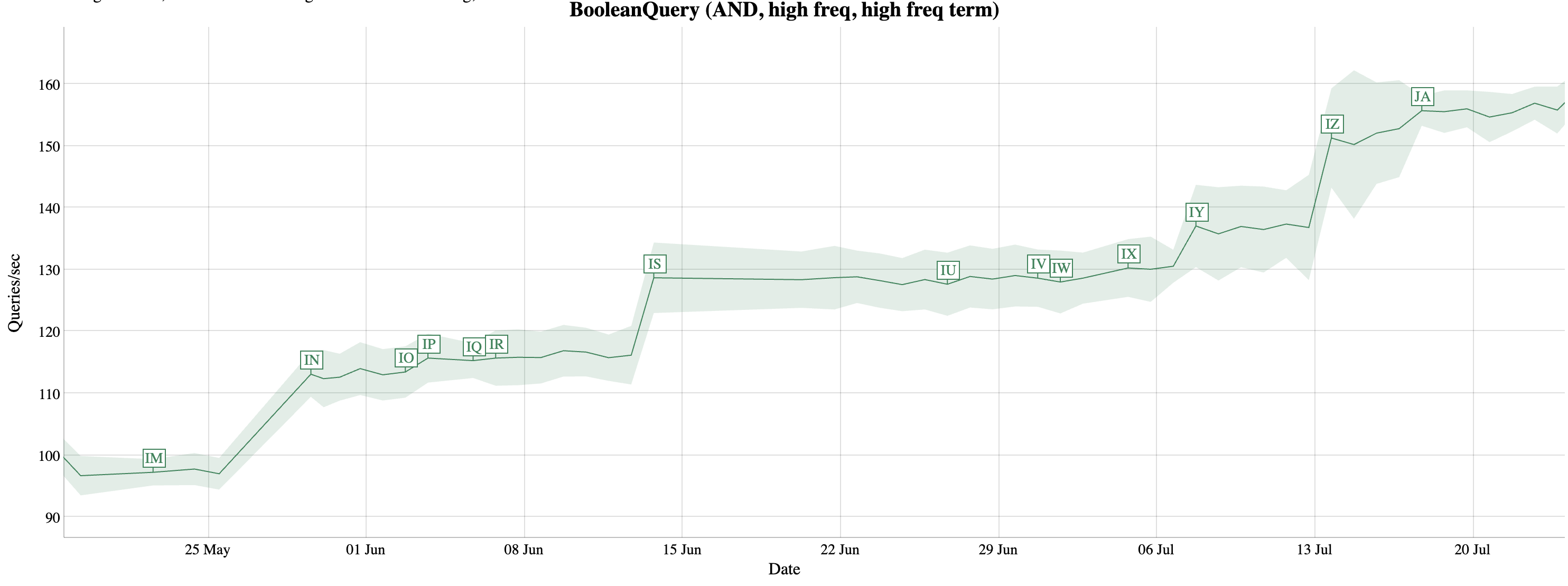

How much did it help? Let’s look at Lucene’s nightly benchmarks over the period of time when this work happened.

Here’s what happened that is related to vectorization:

- Annotation

INis where Lucene introduced the above algorithm for conjunctive query evaluation. - Annotation

ISis a hardware upgrade, no meaningful code changes. - Annotation

IYmadefilterByScorebranchless. - Annotation

IZoptimizednextDocsAndScoresin the case when Lucene encodes blocks of postings as bit sets. - Annotation

JAis wherefilterByScorestarted using SIMD instructions.

Even if we ignore IS, which is unrelated, this is still a ~40% speedup that can be attributed to Lucene’s transition of a more vectorized model for query evaluation.

Conclusion

Despite their more branchy nature, search engines can also take advantage of vectorization to improve performance, even in the presence of pluggable queries (term queries, range queries, etc.) and pluggable scoring models (BM25, TF-IDF, etc.), notably by amortizing the cost of virtual function calls over many doc IDs, using more memory-friendly access patterns and taking advantage of SIMD instructions. By aligning batches of doc IDs to process during query evaluation with postings blocks of the leading conjunctive clause, the amount of extra work that needs to be done compared with traditional DAAT query evaluation is negligible.

If someone ever finds the time, it would be interesting to implement retrieval using compilation and compare performance with vectorization. Something else that I wanted to evaluate but haven’t found the time yet is increasing the block size from 128 to 256. In theory, this should help take further advantage of vectorization at the expense of decoding a bit more data.

I would like to thank Lucene committers Guo Feng and Ge Song who helped me work on this, as well as Mike McCandless for maintaining Lucene’s nightly benchmarks for so many years.

This work will be released in Lucene 10.3.